Table Of Contents

Previous topic

Next topic

NAPI: The NeXus Application Programming Interface

This Page

Quick search

Enter search terms or a module, class or function name.

By the early 1990s, several groups of scientists in the fields of neutron and X-ray science had recognized a common and troublesome pattern in the data acquired at various scientific instruments and user facilities. Each of these instruments and facilities had a locally defined format for recording experimental data. With lots of different formats, much of the scientists’ time was being wasted in the task of writing import readers for processing and analysis programs. As is common, the exact information to be documented from each instrument in a data file evolves, such as the implementation of new high-throughput detectors. Many of these formats lacked the generality to extend to the new data to be stored, thus another new format was devised. In such environments, the documentation of each generation of data format is often lacking.

Three parallel developments have led to NeXus:

These scientists proposed methods to store data using a self-describing, extensible format that was already in broad use in other scientific disciplines. Their proposals formed the basis for the current design of the NeXus standard which was developed across three workshops organized by Ray Osborn (ANL), SoftNeSS‘94 (Argonne Oct. 1994), SoftNeSS‘95 (NIST Sept. 1995), and SoftNeSS‘96 (Argonne Oct. 1996), attended by representatives of a range of neutron and X-ray facilities. The NeXus API was released in late 1997. Basic motivations for this standard were:

An important motivation for the design of NeXus was to simplify the creation of a default plot view. While the best representation of a set of observations will vary, depending on various conditions, a good suggestion is often known a priori. This suggestion is described in the NXdata element so that any program that is used to browse NeXus data files can provide a best representation without request for user input.

Another important motivation for NeXus, indeed the raison d’etre, was the community need to analyze data from different user facilities. A single data format that is in use at a variety of facilities would provide a major benefit to the scientific community. This should be capable of describing any type of data from the scientific experiments, at any step of the process from data acquisition to data reduction and analysis. This unified format also needs to allow data to be written to storage as efficiently as possible to enable use with high-speed data acquisition.

Self-description, combined with a reliance on a multi-platform (and thereby portable) data storage format, are valued components of a data storage format where the longevity of the data is expected to be longer than the lifetime of the facility at which it is acquired. As the name implies, self-description within data files is the practice where the structure of the information contained within the file is evident from the file itself. A multi-platform data storage format must faithfully represent the data identically on a variety of computer systems, regardless of the bit order or byte order or word size native to the computer.

The scientific community continues to grow the various types of data to be expressed in data files. This practice is expected to continue as part of the investigative process. To gain broad acceptance in the scientific user community, any data storage format proposed as a standard would need to be extendable and continue to provide a means to express the latest notions of scientific data.

The maintenance cost of common data structures meeting the motivations above (self-describing, portable, and extendable) is not insurmountable but is often well-beyond the research funding of individual members of the muon, neutron, and X-ray science communities. Since it is these members that drive the selection of a data storage format, it is necessary for the user cost to be as minimal as possible. In this case, experience has shown that the format must be in the public-domain for it to be commonly accepted as a standard. A benefit of the public-domain aspect is that the source code for the API is open and accessible, a point which has received notable comment in the scientific literature.

More recently, NeXus has recognized that part of the scientific community with a desire to write and record scientific data, has small data volumes and a large aversion to the requirement of a complicated API necessary to access data in binary files such as HDF. For such information, the NeXus API (NAPI) has been extended by the addition of the eXtensible Markup Language (XML) [1] as an alternative to HDF. XML is a text-based format that supports compression and structured data and has broad usage in business and e-commerce. While possibly complicated, XML files are human readable, and tools for translation and extraction are plentiful. The API has routines to read and write XML data and to convert between HDF and XML.

| [1] | XML: http://www.w3.org/XML/. There are many other descriptions of XML, for example: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XML |

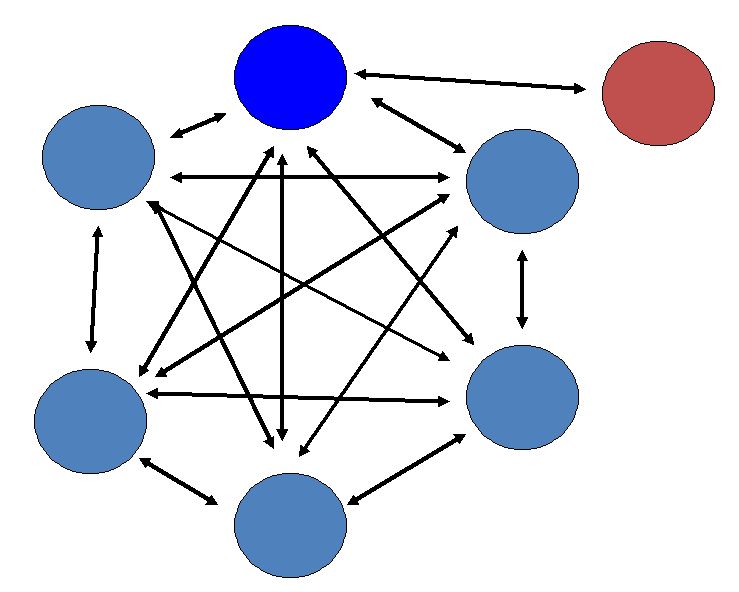

By the late 1980s, it had become common practice for a scientific instrument or facility to define its own data format, often at the convenience of the local computer system. Data from these facilities were not easily interchanged due to various differences in computer systems and the compression schemes of binary data. It was necessary to contact the facility to obtain a description so that one could write an import routine in software. Experience with facilities closing (and subsequent lack of access to information describing the facility data format) revealed a significant limitation with this common practice. Further, there existed a N * N number of conversion routines necessary to convert data between various formats. In N separate file formats, circles represent different data file formats while arrows represent conversion routines. Note that the red circle only maps to one other format.

N separate file formats

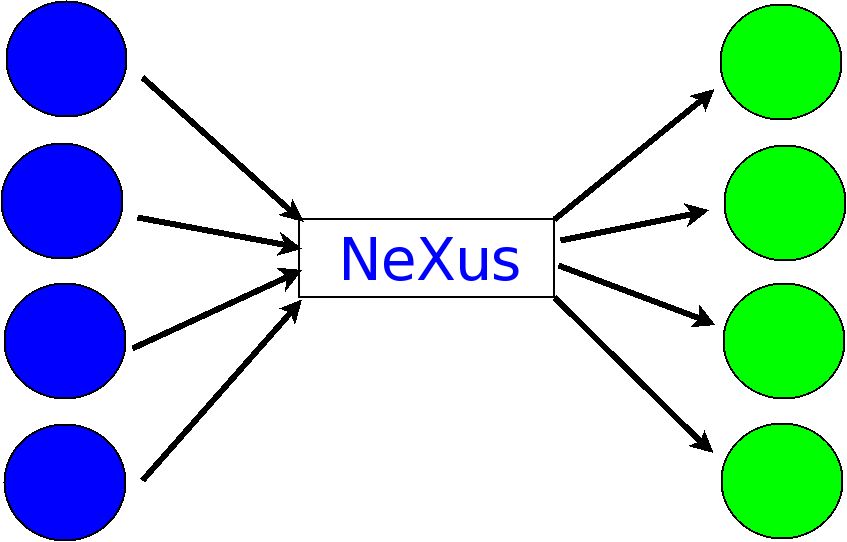

One early idea has been for NeXus to become the common data exchange format, and thereby reduce the number of data conversion routines from N * N down to 2N, as show in N separate file formats joined by a common NeXus converter.

N separate file formats joined by a common NeXus converter

A necessary feature of a standard for the interchange of scientific data is a ` defined dictionary (or lexicography) of terms. This dictionary declares the expected spelling and meaning of terms when they are present so that it is not necessary to search for all the variant forms of energy when it is used to describe data (e.g., E, e, keV, eV, nrg, ...).

NeXus recognized that each scientific specialty has developed a unique dictionary and needs to categorize data using those terms. The NeXus Application Definitions provide the means to document the lexicography for use in data files of that scientific specialty.